WEST RIDGE — In a life entrenched with religious tradition, Jonah Berele was a trailblazer.

When he was born in 1988 it was as Sarah, Miriam and Allan Berele's first-born baby.

But growing up a devout Jew in West Ridge, particularly within the conservative Orthodox community, it wasn't easy for Jonah to come out as a transgender teen.

"At first, I think it was a little bit of an adventure, something she was excited about," said father Allan Berele, a math professor at DePaul. "I once said to her, 'I don't understand what you mean when you say you're a guy.' She said, 'I don't understand it, either.' "

"I hated that she did it, but I have to admit that after she did it, it made her a much happier person. It was very important to her. There's absolutely no question."

On Sunday Sept. 25 Jonah died in Lake Michigan at the age of 27, but friends and family say his legacy isn't over.

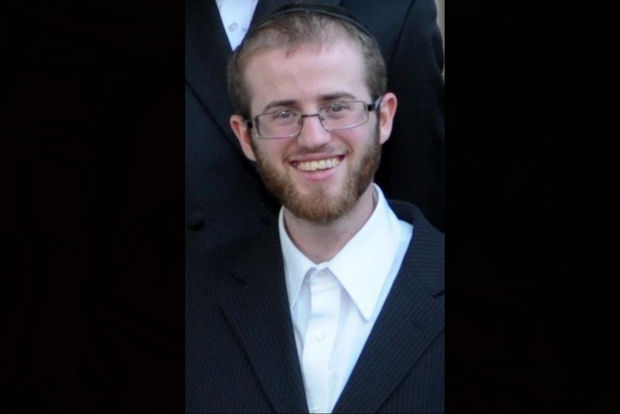

Jonah Berele at a recent wedding. [Provided]

Jonah Berele at a recent wedding. [Provided]

Jonah pressed on and made the decision to be open about his "proper identity," purposely choosing a new name that in many parts of the world was considered gender-neutral, his mom explained.

To those who knew Jonah since childhood, like friend Kate Kinser, it was "obvious" Jonah identified with being male, something he became more open about as he got older and started going to trans-supportive groups at Howard Brown Center.

The change was hard for his family to come to grips with, his parents said, but their love for their eldest child never wavered.

"I never thought of Jonah as a male, I probably did stop thinking of her as a female, I saw her as just as Jonah," his dad said. "I've always loved her, absolutely."

Jonah began taking hormones, sprouted his first beard and started spending more time at the synagogue where his mom worshiped, Ner Tamid Ezra Habonim Egalitarian Minyan.

Linze Rice shares details on the struggles Jonah was able to overcome.

Though still a part of the Conservative Jewish community, his mother said Jonah felt more accepted there.

"The Orthodox community in this neighborhood is not liberal, it is much more interested in conforming than developing a viable philosophy," Miriam Berele said. "I believe that Jonah felt as a person, and as a representative of certain ideas, that there was a lot of rejection coming out of the Orthodox community. ... Jonah didn't compromise values."

It was there, and his diagnosis at age 17 of being diabetic, that helped him come "into his own."

"When I first met Jonah as Sarah, he was, at least in public, withdrawn and angry," Kinser said. "As he came into his own as a diabetic and as a male, he opened up in wondrous ways."

As his mom put it, Jonah had been determined to live an authentic life as just "one of the guys."

On the day he died, Jonah had completed nearly five pages of a letter to author Julia Serano with of a "calm, well-written" response to her book, "Excluded: Making Feminist and Queer Movements More Inclusive," something Jonah's mom said he felt strongly about after feeling "rejected" early on by much of the Orthodox community.

Jonah was a person willing to take a stand for himself and others, people he felt were "down-and-out," his mom said. It was also his generosity and "selflessness" that defined much of Jonas' character, his parents said.

Before the end of his life, the cause and manner of which have not yet been ruled by the medical examiner, Jonah had accomplished at least one major feat he'd long worked toward: becoming a foster parent.

Jonah had obtained his foster care license through the state and for months had worked with and cared for Daniel, an older boy with severe communicative and learning disabilities.

Still, Jonah was determined to improve Daniel's communication, especially in building trust with adults and other kids. Jonah loved to read to Daniel and did it often, and Daniel loved to be read to, Miriam said.

Over time, and with the help of his parents, Jonah bought a condo in the 2200 block of West Farwell Avenue so Daniel could come and live with him full-time.

On the day he died, Jonah and Daniel had gone to Loyola Beach, part of a Sunday ritual they had adopted after Daniel spent the summer playing in a camp at Loyola Beach Park for kids with disabilities.

On most occasions, a friend accompanied the pair, but on Sept. 25 that friend was unavailable.

What happened next was unclear, but Jonah was pulled to shore by someone in a kayak, his family said.

Daniel was found wandering near the beach dried-off and fully dressed, wearing Jonah's backpack which contained his cell phone inside. Emergency responders found the cell phone and called one of the last numbers dialed, Jonas' parents.

At 3:13 p.m. he was pronounced dead at St. Francis Hospital in Evanston.

His father went to identify the body and reported to Miriam that Jonah's "face looked at peace."

Jonah's dad Allan holds a written sheet Jonah made while studying calligraphy one summer. [DNAinfo/Linze Rice]

Jonah's dad Allan holds a written sheet Jonah made while studying calligraphy one summer. [DNAinfo/Linze Rice]

"Until his final breath he gave himself to others and shared his gifts with all his heart and soul," Kinser said of her friend.

Indeed, Jonah was revered by many, and his family said he felt the same of others.

He volunteered to teach chess in schools and taught himself how to weave before then teaching blind and vision-impaired residents at Friedman Place, where he worked, to do it themselves.

At Friedman Place, he was an engaging person who "didn't turn away from anybody" in a way that "made people feel the best about themselves," his mom said.

At his funeral, at least one woman who knew Jonah told his parents he had been "the only one" to believe in her, and she said without Jonah, she would likely be homeless.

He tutored kids in math, volunteered in the children's section of the library and had been recently promoted to a supervisor role at Friedman Place.

He cared about his Far North Side communities of West Ridge and Rogers Park and frequently attended public meetings. He loved to read and write. He was a "genius," Miriam said.

And though Jonah didn't grow to be the woman his parents used to think he might become, he was still their Jonah, caring and loving — and that was enough.

"When all is said and done, the things that I wanted out of Jonah as a woman, I got anyway," his mom said. "Jonah was taking care of people."

Marc Bermann, who knew Jonah through the foster agency, stopped by the family's home on an overcast Friday afternoon before the start of Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year.

Flipping through pictures, Bermann said with all the accomplishments Jonah had made in his first 27 years, he couldn't help but think what the future may have held.

"If you think what he accomplished in such a short period of time, you can only imagine what potential there was for him as a caregiver, as a friend," Bermann said. "An incredible life taken too soon, there's no doubt about it."

For more neighborhood news, listen to DNAinfo Radio here: