If you venture into Manhattan's Chinatown on Jan. 28, you'll encounter a neighborhood flush in red and gold for the Lunar New Year festival. The celebration is just one part of the complicated and evolving history of the neighborhood. These are the essential stories that explain how the Chinatown of today came to be:

1. Chinatown was created in the late 1800s as a refuge for survival.

New York's Chinatown came into being in the 1870s, as the Chinese population rose from approximately 150 in 1859 to more than 2,000 in the 1870s, according to Peter Kwong, author of "The New Chinatown." Many immigrants were driven out of the West due to a violent anti-Chinese movement that was fueled by white anxiety over jobs, as employment collapsed with the end of the Gold Rush and completion of the transcontinental railroad.

Repelled by external discrimination, Chinese immigrants clustered together in a few core streets — Mott, Pell, and Doyers — that eventually expanded into Chinatown.

“This was already an immigrant-heavy area,” said Stephanie Zank, an educator at the Museum of Chinese in America, citing the Irish and freed African-Americans who inhabited lower Manhattan.

Chinese, barred from citizenship and its protections, formed their own internal structures that provided jobs, medical care and housing. A group of merchants created the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association in the 1880s, which functioned as a quasi-local government. Its appointed leader was known as the “Mayor of Chinatown.” Underneath this umbrella, there were roughly three kinds of associations: The fongs, people from similar districts in China; the tongs, business or trade associations; and family clan name associations (e.g. the Lee’s).

2. Before 1965, Chinatown's population was overwhelmingly male.

“In 1900, there were 4,000 men to 36 married women in Chinatown,” Zank said, citing census data. Entering the United States after 1882 was nearly impossible for any non-elite Chinese, but women in particular were left behind. Single and unemployed women were barred as they were seen as prostitutes, who were banned in 1875.

Unmoored from familial ties, men relied on fong associations as substitute families or turned to gambling, prostitutes, and opium, Kwong wrote. Some married American women, but intermarriage rates were extremely low due to restrictive citizenship laws.

“If an American woman had U.S. citizenship, and she married a man from China, she’d lose her citizenship,” said Zank. “Those who did intermarry often married Irish women,” Zank said, explaining that during the turn of the 20th century, the Irish occupied a similar lowly status.

3. Male Chinese immigrants found a niche in "women's work."

Chinese immigrants, shut out from white-collar professions due to discrimination and lack of knowledge or capital, capitalized on economic niches. According to the Museum of Chinese in America's exhibit "With a Single Step: Stories in the Making of America," Chinese immigrants were often poor and barely literate in English, so enterprises that required little capital or literacy were ideal. Since the Western frontier in the 1800s lacked women, Chinese immigrants offered to clean workers' clothes and cook food, which materialized into hand laundries and restaurants that traveled with them to the East coast. Hand laundries were relatively cheap to open and simple to maintain, despite the arduous labor required.

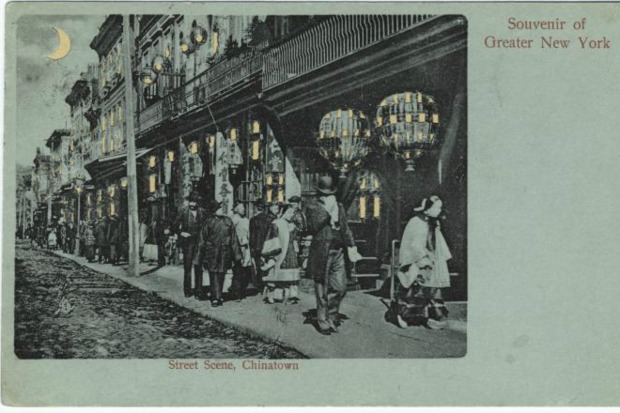

4. Chinatown became a tourist destination with two faces: one an immigrant refuge, another a “usable curiosity” for white tourists.

Soon after the establishment of Chinatown, white Americans exotic-ized it as a space of the "Orientalist Other," leading to a tourist boom, according to the Museum's exhibit. The Chinese capitalized on these stereotypes: Chinese-Americans developed chop suey to introduce Americans to Chinese-American cuisine, which before then had been reviled.

Chop suey nightclubs featuring all-Asian performances catered to white curiosities, such as China Doll at 51st and Broadway, proliferated. Outsized rumors of opium dens and prostitution houses fueled Chinatown's allure, which residents exploited by giving tours of these illicit places to visitors.

“It created some sense of danger to Chinatown ... but it was mostly people trying to make a living,” Zank said. Tourism became an essential economic industry in Chinatown, inextricably linking its two faces together.

5. Chinatown became a site of continuous gang violence in the early 20th century

Given that Chinatown was a poor neighborhood involved in illegal trade, many business owners relied on tongs to provide loans, legal aid, and protection from governmental intrusion. Arthur Bonner, author of "Alas! What Brought Thee Hither" wrote that business owners often lived in their own shops, violating codes requiring separation of commercial and residential spaces.

In addition, the tongs controlled the underground trades of gambling, prostitution, and drug dealing. In 1904, tong factions waged a guerrilla-style cycle of violence against each to vie for dominance, a process heavily reported by media. While the violence existed, the media sensationalized it as a defining aspect of Chinatown.

“A lot of it is exaggerated... [The tongs] did get involved with illegal activity, but ... they were more of a self-help group," Zank said.

6. Almost all of Old Chinatown has disappeared with changing immigration patterns, increased government presence, and relentless market forces.

The end of immigration restrictions in 1965 ushered in a great immigration wave into Chinatown, which by 1980 held the largest community of Chinese in the U.S, according to Kwong.

While they were Chinese, the immigrants were from different regions of China — Cantonese-speaking immigrants from Hong Kong and later Mandarin-speaking Fujianese immigrants. Chinatown expanded into the Lower East Side and Little Italy with the influx of immigrants, many of whom were women funneled into garment factories to support the declining industry, Bonnie Tsui wrote in “American Chinatown: People’s History of Five Neighborhoods.” So many women labored in Chinatown garment factories that they contributed approximately $125 million annually to the New York economy, Tsui wrote.

Chinatown has evolved into roughly two parts: the western front consisting of older Cantonese residents who arrived in the mid-20th century, and the eastern side transformed by more recent Fujianese immigrants, Tsui wrote. The associations, including the tongs, have been outmoded with increased police and governmental presence.

Brutal rent prices have forced the closure of essentially all of Old Chinatown's businesses. While the neighborhood's historic roots have largely vanished from the street, its community thrives by adapting to each wave of changes, continuing the centuries-old immigrant tradition of embracing the future.

RELATED:

► Celebrate the Year of the Rooster in NYC This Lunar New Year

► 8 Things You Should Know About Lunar New Year Traditions