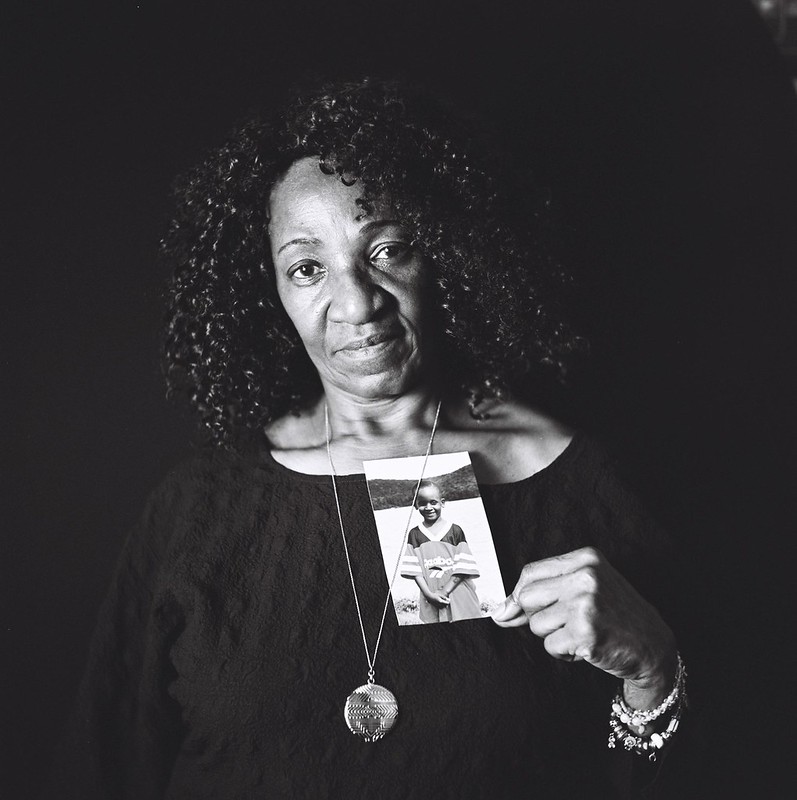

Grief plagues Paula Shaw-Leary three years after her son, Matt Shaw, was killed, she said. DNAinfo/Aidan Gardiner

EAST HARLEM — Matt Shaw wasn't supposed to be in New York in July 2012.

Shootings earlier that summer rattled his mother, Paula Shaw-Leary, so she sent her youngest of seven children, a 21-year-old finance major who had just been accepted to SUNY Albany for a masters degree in economics, to his sister's home in Georgia.

"I just for some reason had this feeling: Get him out of here, get him out of here, get him out of here," Shaw-Leary said. "But he wanted to come back and I couldn’t keep him."

Shaw was fatally shot in a case of mistaken identity outside the AK Houses at Lexington Avenue and East 128th Street about 1:30 a.m. on July 5, 2012, shortly after his return to the city.

Three years haven't eased Shaw-Leary's grief. On better days, she eats her breakfast and has strength enough to do some vacuuming and dusting.

But other days, especially when she hears about a new shooting, she relives each dark detail of her son's death.

“Most days, you’re all right,” Shaw-Leary said. "And then, some days, you just go back to day one."

Matt Shaw took several selfies of himself at his graduation from Le Moyne. He had just been accepted into a masters degree program. Instagram/@mattiverson

Shaw-Leary, who grew up in Jamaica and works in hospitality at the Times Square Marriott, last spoke to her son over the phone about 12:30 a.m. on July 5. He wanted to extend his curfew.

She relented, hung up the phone and raced to grab a plate of fried chicken and fries from the hotel's second-floor kitchen before it closed at 1 a.m.

Meanwhile, Shaw stood outside the AK Houses with friends when Khalid Rahman, 20, approached.

They'd met a year before by chance when Rahman had been stabbed and was running through East Harlem until Shaw called an ambulance for him, friends later told Shaw-Leary.

But that night, Rahman thought he saw a man who had recently insulted him in front of his daughter and opened fire, friends told Shaw-Leary.

A bullet hit Shaw as he tried to flee. He left a small trail of blood on Lexington Avenue to where he collapsed.

“I ran over there and saw him lying there, bleeding," a friend said the morning after the shooting. "He looked gone, but he was still breathing."

A group chased after the gunman as he fled, firing back at them, prosecutors said. He was arrested eight days later and eventually pleaded guilty to manslaughter.

News of the shooting quickly traveled to Shaw-Leary, who had just grabbed her dinner.

“They were calling me to tell me he’d got shot. I just went crazy. I bugged out. I started pacing the hall. Everyone was asking me, ‘What happened?’ I couldn’t even explain to them what happened,” she said. “‘No, no, my God, no, no, no, no.’ That’s all I kept saying.”

Shaw-Leary raced to Harlem Hospital, where Shaw had been taken. Then she waited.

“I thought, ‘OK. Everything is going to be OK. He was shot in the midsection. How hard can that be? How fatal can that be?’”

But time ticked by and doctors still weren’t rushing over to reassure her. Each passing minute pounded into her a grim lesson about hospitals:

“It’s not good news when nobody comes fast.”

Finally, a doctor came.

“I’m sorry. We couldn’t save him,” she told Shaw-Leary in a soft voice.

“I screamed. I screamed so hard it was ridiculous,” the mother said.

The people with Shaw-Leary tried in vain to soften the immense shock.

“First they wanted to sit me down. I didn’t want to sit down. Then they wanted to give me water. ‘I don’t want no water.’ Nothing,” Shaw-Leary remembered.

She finally managed to calm herself enough to go see her son’s body lying in the operating room. She lifted up the blanket and saw her bloodied boy lying there with his eyes wide open with tubes sprouting from his chest and mouth.

“I knew there was nothing they could’ve done. He bled out. There was a lot of blood on the table,” she said.

There was so much she didn’t understand. Why had her scholar just been killed? What happened to her "little buddy" who would call her all the time, even just to ask for Snickers bars. “What happened? What happened? What happened?” she pleaded.

“Why your eyes are open? Why you didn’t close your eyes?”

“I remembered, there’s a saying in my country, in Jamaica, if a person dies and their eyes are open, they waiting for someone. It dawned on me, he’s waiting for me to close his eyes. So, I closed them for him and said my goodbye. I told him I loved him,” Shaw-Leary said.

She took a few photos of Shaw and walked out of the hospital where she and an ever-growing crowd stood until daybreak before returning home.

The bleary hours that followed were clouded by grief so intense that it loomed over her for months.

“I realized he won’t be coming to the door anymore. Then, you start picking up the pieces and the tears come. I remember, I cried a lot,” she said.

Paula Shaw-Leary holds her favorite photo of her son Matt Shaw, who was killed in 2012. DNAinfo/Aidan Gardiner

Shaw-Leary, who grew up a devout Jehovah’s Witness and openly prayed every day, wavered from her bedrock faith.

“I just stopped praying. I figured it didn’t matter anymore. I prayed and look what happened. It just went out the door,” she said.

She started praying again when her daughter said she saw Shaw in a dream. That helped. As did a new dog, a small burst of yapping white. And other modest rituals over the ensuing months and years eased the constant ache.

She regularly tucks Shaw's favorite foods — Golden Krust beef patties, pepperoni pizza, pot pies, Snickers bars — into Tupperware bins and sets them atop his silver urn on a living room shelf surrounded by photos of him.

“That’s why I didn’t put him in the ground. If it rained, snowed — bad weather — I’d be tormented. I’d be, ‘Oh my God, he’s wet. Oh my God, this. Oh my God, he’s cold.’ I don’t want to go through that,” she said.

“So he’s in there. And I could talk to him. ‘How are you doing today? I miss you.’ Then when I give him his meal, ‘Enjoy your meal. This is for you.’ I let him smell it and put it on his urn,” she said.

She replaced the bed in his room with a black leather couch so she can watch her shows and the news amid his 28 trophies, his Nikes, his academic accolades and other mementos.

A photo of him in a black graduation gown is tucked in the bottom left corner of the television’s frame.

“Life’s changed so much. You don’t have the same enthusiasm for anything. You wake up — OK — and you try to get through the day,” she said.

But despite that, or maybe because of it, she’s magnetically drawn to other shooting victims like the mothers of Tysha Jones and Cheyenne Baez.

And every day she scans the news just to find information about new shootings.

“Since my son’s death, I buy the paper every day just to see who got shot and how many died. That’s all I look for. That’s all I read.”

According to the NYPD, more than 3,748 people have been shot in New York since Jan. 1, 2013 and each new shooting reminds Shaw-Leary of her son's death.

“It just brings you back," she said, "brings you back to day one.”