After Jackie Robinson West got stripped of its title and the guy who filed the first formal complaint got death threats, Forbes.com contributor Kelly Richmond Pope wrote a column posing an ethical question close to my heart:

Is a whistleblower a hero or a villain?

“As I watched the community’s varied reactions, I grew reflective on what I tell my students every class meeting about reporting fraud, and I began feeling very conflicted about how society truly feels about whistleblowers,” wrote Pope, a fraud researcher who teaches "Principles of Forensic Accounting" at DePaul University.

“Do we really applaud them and hold them in high regard, or do we despise their willingness to come forward and secretly think they have ulterior motives not for the greater good? The public’s reaction to the JRW case makes me think the latter.”

During my reporting career, I’ve had many encounters with the so-called “no-snitch code,” a pervasive cultural phenomenon that has had negative consequences in the street and in the police department.

And while reporting on the Jackie Robinson West cheating scandal, I encountered an overwhelming reluctance to publicly blow the whistle on the adults whose actions ultimately got the U.S. title stripped from a great bunch of young ballplayers.

“I can’t be seen as a snitch. No way. That’s just something we don’t do in our community,” one source told me during months of conversations about the lengths Jackie Robinson West officials went to build a super team of ringers with the goal of winning the Little League World Series. “I’m worried about people breaking into my home. I’m worried about my family.”

It’s a refrain I’ve heard before while writing about how the no-snitch code prevents police from arresting and convicting shooters. The decision to blow the whistle ultimately depends on whether a person is willing to potentially risk personal sacrifice — or bodily harm — for a greater good.

Pope ended her column with a Shakespearean query: “As I get ready for Monday’s lecture, what do I tell my students? To whistleblow or not? That is the question.”

I wanted to know what a bunch of future CPAs studying ethics had to say about the matter and invited myself to class.

And to make things more interesting, I brought along Chris Janes, the guy who first alleged in an email that Jackie Robinson West used suburban ringers during the team’s title run.

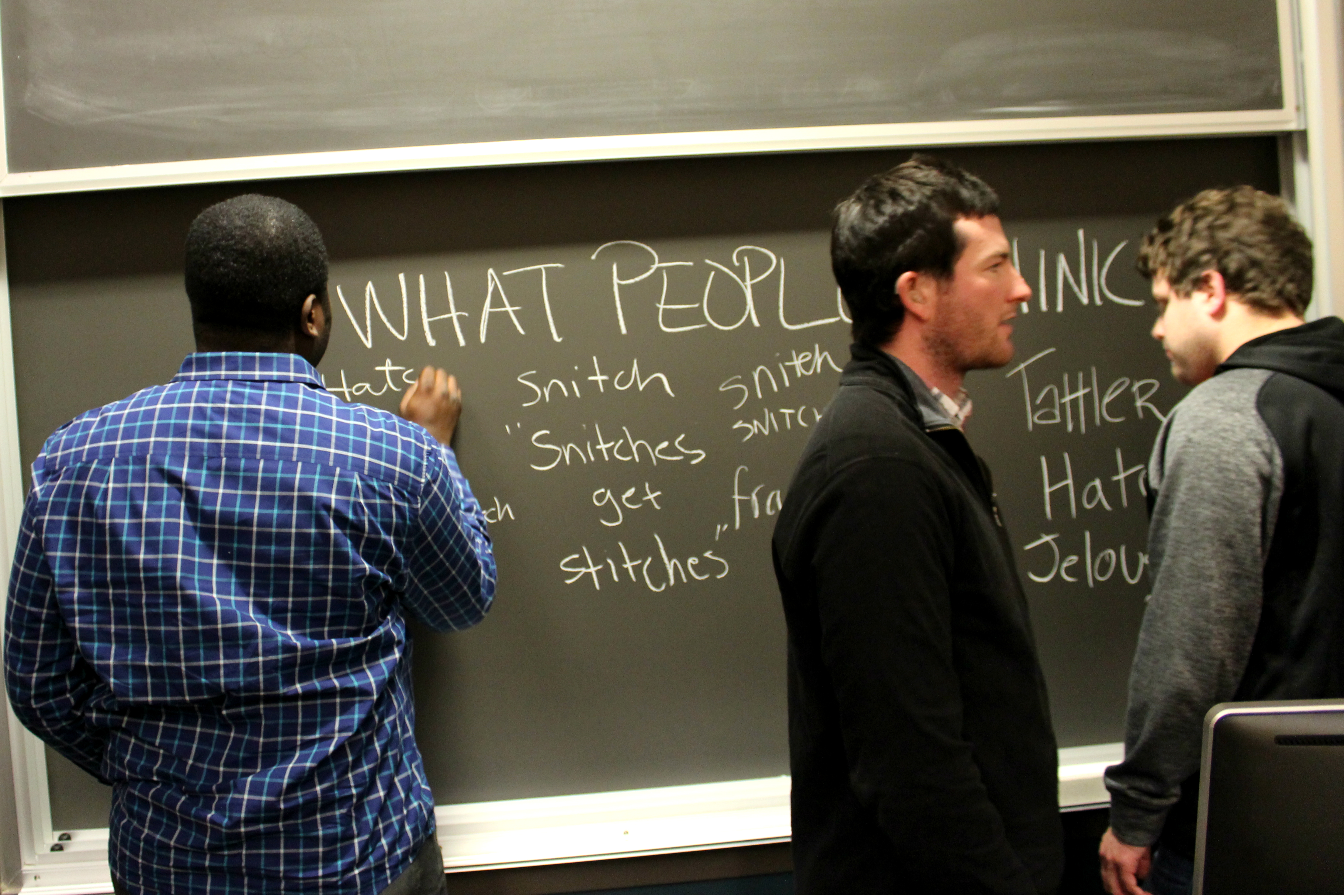

Class started with an exercise. On one blackboard, students were asked to write, “What people think” it means to be a whistleblower.

Most students wrote “snitch.” One wrote “hater.” Another wrote “rat.”

On a separate blackboard, students wrote their thoughts on what it means to blow the whistle on wrongdoing.

They wrote: “truth,” “justice,” “moral,” “fair” and “doing what they need to do.”

And for the next two hours, the class engaged in a conversation with Janes about how he decided to file that formal complaint about Jackie Robinson West’s roster.

He told the class that, yes, the fact that Jackie Robinson West beat his league’s team 43-2 during the sectional tournament did bother him and make him suspicious about the team’s legitimacy. But it wasn’t until he saw “evidence” on the Internet — suburban mayors and a congresswoman claiming Jackie Robinson West players as hometown heroes — that he felt blowing the whistle was the right thing to do.

Not all his pals agreed.

Janes said he nearly got in a fistfight with of one his best friends who had a different plan for leveling the Little League playing field.

“My very close friend said, ‘If JRW does this and they’re going to kick our a--, then I know five, six, seven kids we can get [fake] addresses for and never let this happen again,’” Janes said in class. “I said there’s no way we are going to change the fundamental way we do things because one group of people does it. We almost came to blows. People had to step between us.”

Janes told the class that he weighed the potential personal consequences of coming forward with allegations against the good it might do to preserve a level playing field in Little League baseball, and decided it was worth the risk.

But, as things turned out, his hypothetical worst-case scenario wasn’t nearly as bad as what actually happened after Little League took action.

“I had no idea it would be this bad,” Janes said.

People called him a racist, they threatened his life, rattled his wife and forced his boss to keep him from coming to work for several days because angry people called and showed up looking for him.

“Do you feel supported?” Pope asked Janes.

And Pope said that he did feel support but ultimately “the angry voices were the loudest.”

I asked the class of future accountants whether they would “snitch” or look the other way if they were in Janes’ position.

Ten students said they would blow the whistle, and 11 others said they’d look the other way.

Just a handful of others said they couldn’t decide.

Then, we took another survey: If they witness a shooting, would they cooperate with police and testify in court to help convict the person who pulled the trigger?

Nine students said they’d identify the shooter, and three said they would keep quiet. The majority of the class, a culturally diverse group of well-spoken students who may be corporate America’s financial gatekeepers one day, said that they just couldn’t honestly answer the question with certainty.

“Even if you know something is wrong, and you feel it’s so wrong that you are totally going to say something — and even if something involves your family or involves people you’re very closely — even though you think you might [blow the whistle], you might not actually do it,” one undecided student said.

And she’s right.

For people living in violent parts of Chicago, the decision to blow the whistle on things with far higher stakes than baseball boundaries might mean risking their own lives for the greater good of their neighborhood.

And for the students in Pope’s class, that might mean standing up to a powerful CEO that they catch cooking the books, or standing up to a restaurateur laundering money for the mob, to protect their own integrity in the face of losing their job, or worse.

The conversation in Pope’s class put Janes and his blowing the whistle on Jackie Robinson West in a broader context: No matter the situation, the decision to snitch or not to snitch ultimately comes down to whether a person has the guts to take a moral stance publicly when to do so could have a negative impact on them personally.

A student said the discussion reminded him of a saying that he’d heard before, a famous Edmund Burke quote that gets to the heart of the matter.

“The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.”

Class dismissed.

For more neighborhood news, listen to DNAinfo Radio here: